Editor’s Note: This essay also appears in The Line Issue 11.6 (June 2024); subscribe to The Line here.

Everyone should believe in something. I believe I’ll have another beer.

A friend of mine, an Eastern Orthodox deacon, had this statement on a bumper sticker on his pickup. Fed up with the inanity of the cliché that “it doesn’t matter what you believe, just so you believe in something,” he chose ridicule as the way to refute it. While some thought it impious of him, he found it opened floodgates of responses, exposing the difficulties that many people have with the concept of belief.

At a basic foundational level, many divide the world into that which is fact and that which is belief. It is an understandable mistake, given society’s belief that there are self-evident things and other things which some people believe. The latter, such

as religion, the paranormal, the future, alternate non-Western healthcare, political utopias and UFO’s, are optional. The former are things which can be scientifically verified or almost universally accepted or predictable, like sunrise.

While there may indeed be facts out there, the problem is that we only can know what we perceive, and that may or may not coincide with the actual facts. The sights which you see may be a mirage, or hallucinations, or distorted by faulty vision or by your brain misinterpreting the message sent by your eyes. The slight tickling feeling under your shirt may be a tick, spider or bug, or your brain imagining it, based on a memory of how a woodtick felt yesterday, or perhaps a mild case of poison ivy. The point is, the only way we know things is by trusting our perceptions or the perceptions someone else has shared with us.

Those perceptions are based on belief, not objective fact. Science even refutes many of these. What we perceive, for instance, as a solid table, is apparently a massed crowd of dancing atoms. That which the disciples, huddled in a room post-Resurrection, perceived as a solid wall, may have been a dimension turned sideways, allowing the atoms of the resurrected Jesus to flow easily through the atoms of the wall, and appear to the disciples inside.

We all operate on scads of these beliefs, and need to in order to function. I believe when I get out of bed in the morning and my feet hit the floor, that the floor will hold me. Throughout the day, hundreds of such beliefs will make it possible to achieve my daily tasks without extensive agonizing about how the world around me will act; air and water will be available, gravity will anchor me to the ground, and my eyes will not lie to me in identifying where the stairs are.

Thus, everybody does believe in something, many things in fact. If they didn’t, they would be terrified to get out of bed. The problem comes in thinking that we can rely on some beliefs as absolute fact while other beliefs are relegated to speculations or guesses. This is simply a corollary of the western worldview dividing everything into that which is agreed upon as obvious and that which western society regards as unverifiable by their accepted methods of vetting such matters. This very attitude can be seen as unverifiable in itself.

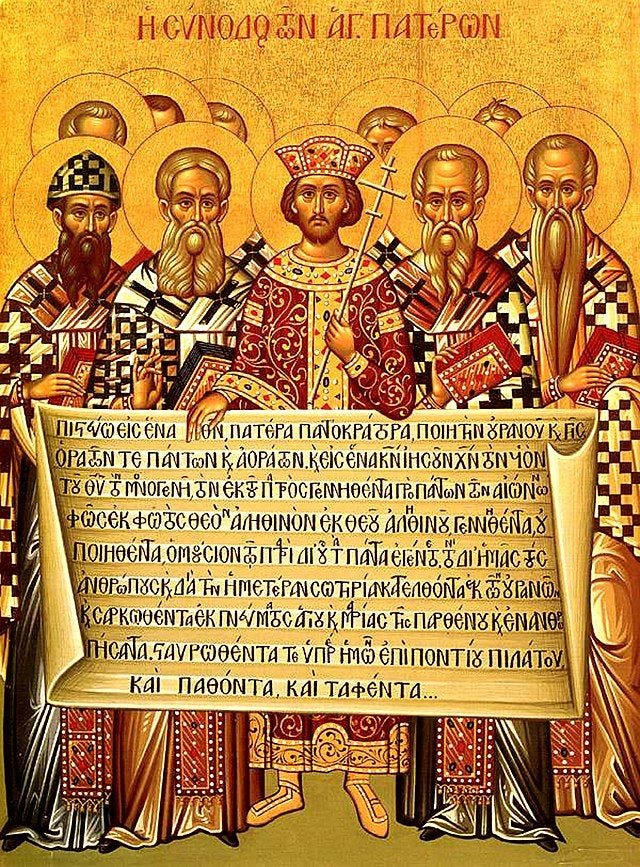

Ultimately, instead, everything must be accepted as a belief, and life proceeds based on these beliefs. That does not mean everything is a true belief. We are currently familiar with this because we can no longer rely on media to tell the truth, nor are we so naïve as to swallow everything stated on the internet and social media. But the process has been around for a long time. A typical example would be, as members of a jury, having to decide between two opposite versions of a set of events, both claiming to be true. Religious belief is no different. When we profess the Creed, we are stating an interconnected set of beliefs in the Triune God, the sacraments, the resurrection, and the historicity of the Incarnate Christ.

Yet the Creed enters a dimension beyond assenting to central beliefs about the Christian Faith. To be a Christian is much more. Indeed, it is possible to have a comprehensive and expert understanding of Christian doctrine, yet to reject or be indifferent to Jesus Christ, even to be an atheist. It is very important to approach the Creed for what it is. In the historic Liturgy of the first millennium and still in Eastern Christianity, it begins with the celebrant proclaiming, “Let us love one another, that we may with one mind confess the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

The Creed, which opens the specifically Eucharistic part of the Liturgy (the “Mass

of the Faithful”) puts love and unity (“one mind”) as the keynote theme of the Creed, rather than a list of dogmas. It is unfortunate that the 2019 Book of Common Prayer chose instead to use the words, “Let us confess our faith in the words of the Nicene Creed,” completely missing the basic meaning of confessing the Creed (and celebrating the Eucharist) together in love and unity. “If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing” (1 Corinthians 13:2), as St. Paul eloquently notes.

It is the distinction between knowing about Jesus Christ and knowing Jesus Christ. Baptism incorporates us into the Body of Christ, not into a society of dogmatists. The rest of our life after baptism is lived in the context of daily receiving and sharing the love of God, in union with Christ and our baptized family of fellow believers, immersed and absorbed in the very person of our Lord.

The various doctrinal statements of the Creed remain important and true. The distinction in knowing is not at all a validation of the previously quoted cliché that “it doesn’t matter what you believe.” But doctrinal affirmation does not replace love and unity, it confirms it.

And if it is important to believe that the floor will be solid enough to support your body when you get out of bed, it is certainly more important to believe in

the historical reality of the Resurrection. Yet all we do and believe begins with the love of God bestowed in baptism and renewed every day, in the everlasting act of uniting us to him and our brothers and sisters in Christ. My trust in that love today and forever sustains me, as the love flows through belief and action, in the loving Eucharistic path of union with Christ.