This essay was first published at Catechetical Mystablogy

1 Church of England liturgy now

The authoritative liturgy of the Church of England, despite a preponderance of sanctioned alternatives, remains the Book of Common Prayer in its 1662 edition. This traces its origins back to the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer’s original Prayer Book of 1549. A survey of its contents reveals Cranmer’s intentions to bequeath within its pages a concise but comprehensive rule for the spiritual life of the English people. The Prayer Book prescribes daily, the communal recitation of Morning and Evening Prayer, in the course of which the Psalter is read once monthly and the whole Bible annually; weekly, the respective fast and feast of Friday abstinence and Sunday Holy Communion, with a Litany to be prayed then and on Wednesdays to mark that day’s penitential character; seasonally, the patterns of the Church, civic and agricultural year, including the marking of Lenten penance and fasting, prayers to mark the accession of the Sovereign, and pleas and thanks for good harvest; annually, the celebration of the saints of the Church; and, at the scale of the human lifetime, the orders for baptism, matrimony, visitation of the sick and dying with private confession and communion; and finally, when occasion demands, the order for ordination of those to serve as deacons, priests and bishops of the Church. Holy Communion is at the centre of the book, its pole star, as it is at the centre of the life of the Church and of every Christian; baptism is closely oriented towards it, and together these make the two sacraments “generally,” which is to say universally, necessary for salvation. Such is the outline of the Christian faith lived according to the Prayer Book rule, and it is a life unapologetically liturgical. The trappings of the liturgy, such as ornaments of the church and ministers, liturgical furnishings and orientation, and the use of organs and choirs have varied over the centuries and caused much debate, even to the extent of bloodshed. But the Anglican way, as the kind of Christianity derived from Canterbury came to be known, is indisputably liturgical. The Prayer Book is not merely an antiquarian curiosity to be scoured for proofs of doctrine: it is the guidebook for the Christian way of life, written not just to be read, but to be used.

2 Opponents of liturgy

The liturgy of the Church of England has not, however, enjoyed universal approval over the centuries. For many loyal to Rome at its original propagation, it had gone too far into the realm of popularism, likened by one wit to a “parlour game” in comparison with the Latin rite of old. In principle, Latin was replaced with English on the grounds of being “a tongue not understanded of the people,” as the Church of England’s 24th Article of Religion has it. A worthy principle, surely: but when imposed on the Cornish and Welsh, for whom Latin was better “understanded” than English, a principle confounded in practice. For that matter, the English of the Prayer Book, in those centuries long before the homogenising effect on language of audio broadcasts, grew more distant from the English people spoke the further the book travelled from London. Not that most could read it anyway. We cannot pretend that the English Reformation was a grassroots movement: it was imposed from above by an intellectual elite on an often begrudging people who valued their old ways. Nor can we pretend, however, that the English liturgy marked an absolute breach with those old ways to the extent of complete unrecognizability. The principle behind Christian life in English remained liturgical and retained the essence of the older tradition.

Indeed, it is precisely the continuity between the Prayer Book and the older tradition which incurred ire from the other, opposite quarter. If those loyal to Rome scorned the Prayer Book for straying too far from tradition, there were yet many keener sons of the Reformation who scorned it all the more for not straying far enough. From 1553-1558, it was banned by the Roman Catholic Queen Mary on the former grounds; exactly one hundred years later, from 1653-1658, the Puritan Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell banned it on the latter. Worship, the Puritans thought, should be guided by the Bible alone. Liturgy was a merely human tradition, constraining genuine and free entreaties to God. The order of bishops, priests and deacons was also a human conceit, to be abolished. Henceforth, people could worship God as they wished, as long as it was not according to the Book of Common Prayer.

In the modern Church of England, more than in other Anglican provinces, there are so many permissible variations on the liturgy that in many churches, any remnants of the Prayer Book tradition are barely perceptible, if at all. In some quarters, the Puritan perspective has won. Even the official organs of the Church have conceded much to the Puritans’ rhetoric, blithely deploying phrases such as “worship styles” and multiple “traditions” within the Church, as though it is simply common sense to suppose that liturgy is nothing more than a take-it-or-leave-it matter of personal taste. Some prefer Evensong, some prefer Messy Church or Celtic praise: and harm none other, do as thou will. So, hostility towards the traditional liturgy of the Church, whilst properly a subject of theological dispute, has been shifted somewhat disingenuously into a polarity between sunny-dispositioned, easy-going liturgical liberals for whom anything goes, versus Prayer Book-carrying old grumps of the retired Colonel type. In an age obsessed with “optics,” the victor for the attention of desperate bishops is not hard to predict.

Was Cranmer, then, on the wrong side of history? Were our forebears in the faith rigidly attached to the dead repetition of words, slaves to man-made tradition? Is liturgical worship something to be conceded to the elderly 8am congregation until they die out, then gladly disposed of as the Church enters a bright new dawn of spirit-filled freedom? Is liturgy, in short, a matter of passing and possibly bad taste, or is there something lasting and God-given about it? To find out, we will need to consider the origins of worship.

3 Ancient Jewish Liturgy

Since the exile from Eden, the defining aspect of worship offered to God has been sacrifice. Prevented, for our own safety, from re-entering God’s presence by an angel’s sword of fire, humans made burnt offerings of animals in the flames as our representatives. The second human act recorded after the exile is the sacrifice made by Cain and Abel, showing how God receives such sacrifices as are made with a true heart (Gen 4:3-4). After the flood and subsequent renewal of creation, the first thing Noah does is to set up an altar and offer sacrifice (Gen 8:20). Abram set up an altar on arriving at Bethel (Gen 12:8). In time, God would liberate the Hebrews under Moses by means of the sacrifice of the first Passover lamb. He would later give detailed instructions in the Law for proper sacrifice, stressing the offering of blood as the life-force of the animal (e.g. Ex 12:13). Eventually, in the time of King David, the Temple was designed as a permanent place for making such sacrifices and built under his son, Solomon, who dedicated it with thousands of sacrifices (1 Kings 8:61).

Sacrifice, which literally means “making holy,” was and remains the purpose of Israel’s worship: the sanctification of creation and restoration to that harmony and oneness with God that was lost at the Fall. The Divine Word meticulously lays out the orders, which is to say the liturgy, for this divine service throughout the Torah and beyond. The precise dimensions of the Ark of the Covenant and all its furnishings, including images of gold, are included in the divinely given blueprint. The plans for the Temple, too, were handed from David to Solomon “in writing from the hand of the Lord” (1 Chron 28:19). As the Temple was prepared, the Psalms became God’s gift to David and his line for recitation at the daily morning and evening offering of incense there. Musical instruments, including cymbals, strings and horns, were used in offering worship to the presence of God as the Ark was brought into the Temple, there was communal recitation of a liturgical formula from the Psalms, “Give thanks to the Lord, for He is good, for his mercy endures forever,” and the Temple was filled with smoke, possibly incense (2 Chron 5:11-13). The worship of the ancient Jews was sacrificial and liturgical, not as a matter of personal whim, but as decreed by God.

4 Early Christian Liturgy

Even granting that ancient Jewish worship was ritual and liturgical, one may legitimately ask whether Christian worship should also be so. Did not God announce through his prophets his hatred of empty ritual, vain sacrifice and insincere marking of feast days (e.g. Hos 6:6, Am 5:9-27, Mic 6:1-8)? Indeed so: but only of the empty, vain and insincere kind! Holy writ cannot contradict itself so baldly as in one breath to prescribe feasts and sacrifices and in the next to deny them. God is not fickle: in His eternal light there is no shadow of turning.

This brings us to the controversial and sensitive question of the relationship between the Old Covenant and the New. To what extent is it one of continuity or of abrogation? Answering either way causes problems which have historically contributed to the Christian persecution of Jews. We might say that, since the Temple was destroyed by the Roman Empire in AD70, Christian worship is the continuation of that Temple worship, replacing the hereditary Jewish priesthood with the Apostolic priesthood instituted by Christ; or alternatively, that the worship of the Temple was definitively ended, never to be resumed. In either case, it is hard to escape from some form of “supersessionism,” that is, the claim that Christianity has replaced Judaism. Aside from the lamentable historical consequences of either perspective, the latter additionally implies that God has withdrawn the Old Covenant, and that His promises to the chosen people were only provisional: in other words, the Jews are no longer chosen, and God has rescinded His promises. This seems doubly objectionable, and while it is not a question I can hope to answer here, it would be incautious to pass it by without comment, especially since those who hate the Jews will grasp for any ammunition they can find.

Evidence suggests that the early Christians considered themselves inheritors of the Temple tradition rather than its abolishers. It is clear from Scripture that Jesus took part in Temple worship, and the Apostles, continued to do so after He had died, risen and ascended. St Peter preached in Solomon’s porch (Acts 3:11). St Paul took a traditional Jewish ascetic vow (Acts 18:18) and went to the Temple to complete it with an offering, only to be accused of having taken gentiles within (Acts 21:28); while there, he had a vision of God while praying (Acts 22:17). All this is indicative of the very much Jewish identity and practice of the early church in Jerusalem.

When the Apostles gathered in AD 49 at what is known to posterity as the Apostolic Council in Jerusalem, they discussed the extent to which gentile converts should observe Torah. The city’s first bishop, St James, who presided at the Council, cited the prophet Amos (Acts 15:16-17, Amos 9:11-12), through whom God promised to return and rebuild the Temple, “so that the rest of mankind,” i.e. the gentiles, might “seek the Lord.” To this end, James decreed not that the gentile converts should simply ignore the Law altogether, but that they observe only those parts which apply to non-Jews, namely abstention from “things polluted by idols, sexual immorality, things strangled, and blood” (Acts 16:21). Circumcision would not be necessary for them, but their destination was the reconfigured Temple, and the liturgical worship for which it both literally and figuratively stood.

The first large tranche of Christian converts reported in Acts, around three thousand in number, observed a mixed practice of worship in households and in the Temple. St Luke tells us that they “continued steadfastly in the apostles’ teaching and fellowship [koinōnia], in the breaking of bread, and in the prayers… continuing daily with one accord in the Temple, and breaking bread from house to house” (Acts 2:42, 46). One sometimes hears talk of a primitive, pre-liturgical Christianity, bearing a remarkable resemblance to modern house-church movements, where fellow Christians casually gathered for a prayer meeting including scripture reading and a meal. This is misleading on both textual and archaeological grounds.

Textually, the word “fellowship” is koinōnia, used also to indicate Holy Communion; further, “prayers” in the Greek is prefaced with the definite article — “the” prayers — hence more likely referring to specific liturgical prayers than to ad hoc ejaculations. The worship was Eucharistic, and required an Apostle to be present, rather than the lay-led service typical of modern house churches. Further, the numbers recorded as attending such worship imply that only the large houses of wealthy people might be used to this end. St Paul’s stern admonition to the Church in Corinth about turning the service into a drunken feast — “Do you not have houses to eat and drink in?” (1 Cor 11:22) — suggests that it took part in some separate room from normal domestic use.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest Christians worshipped not only in large houses, but also in the catacombs and at the gravesides of martyrs, and even in bathhouses, as need arose in times of persecution. There was no particular emphasis on the domestic setting, as though the early Christians were deliberately opposing themselves to the liturgical practice and sacred space of their Jewish contemporaries and forebears. On the contrary, the desire to pray at the sites of martyrs’ relics suggests a developed sense of sacred space in continuity with Second Temple belief and practice. Liturgical furnishings were also in use. The earliest extant evidence of an actual church dates to AD 230, including an elaborate mosaic floor and dedicated space for an altar and the use of specific eucharistic chalices adorned with the sign of the Cross is attested to by Tertullian at the beginning of the second century.

There is a far clearer continuity between early Church worship and the ancient liturgical worship of the Temple than there is to modern house church groups. Christian worship was grounded in the breaking of the bread, which the earliest tradition ascribes only to the Apostles and their chosen successors, and which originated in the context of the Passover. Christ offered Himself on the Cross as the new Passover lamb, and the means He gave His Church of participating in that offering was the Eucharist He instituted the night before He died. Given that the Last Supper itself, as a part of the Passover celebrations, was itself a liturgical celebration, it should be unsurprising that the Apostles commissioned to continue that celebration should also do so liturgically.

By the mid-second century, Justin Martyr in Rome alludes to established liturgies of baptism and the Eucharist; slightly later, Origen and Clement of Alexandria refer to comparable practices in the Greek-speaking churches; Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem, makes extensive reference to liturgical practice in the 4th-5th centuries. Although there is no extant example of complete written liturgies in Apostolic times, the Didache composed around AD 60 comes close, and it is more reasonable to suppose a continuity between the liturgical practice of the Jews at the time of the fall of the Temple in AD 70 and that of Christian churches attested as little as 80 years later than to suggest on the basis of an absence of evidence that Christians of Justin Martyr’s generation deviated from presumed primitive apostolic practice and plucked their liturgical practice from thin air. That the supposed apostolic practice of casual, non-liturgical, non-hierarchical house church meetings so neatly conforms to modern sensibilities should further make us doubly suspicious of it.

5 Liturgical Britain

We must skip through some centuries if this post is ever to reach Britain’s shores. By the time St Augustine had reached Canterbury in AD 596 to bring the Roman hierarchy there, there had already long been Christian communities. There is record, for example, of British bishops present at a Church Council in Arles in AD 313. The older British Christianity was of a monastic character, influenced by the ascetic desert fathers of Egypt via the works of John Cassian, and based mostly in the hard terrain of the western isles. The monks’ round of worship stressed the old Temple practice of recitation of the Psalms, in some cases the entire psalter being read every week. The Roman envoys, after much and bitter dispute about the dating of Easter, conformed the British Kalendar to their own, adding many native saints to its roll.

By the high Middle Ages, the recognisable round of daily Mass and offices sung by robed choirs with due ceremonial was well established. Its worship was undoubtedly beautiful, but the Church itself was not without corruption or fault. Those faults were pointed out perhaps too emphatically by the Augustinian Friar Martin Luther in the early sixteenth century. The recent advent of the printing press carried his objections to England, where they found cultured sympathisers. King Henry VIII, however, was not one of them. He may have been a monster and a wife-killer, but he had no intention of breaching God’s law or leaving God’s Church. It is commonly said that he broke from Rome on the issue of a divorce. This is not so. He sought an annulment, that is, the proclamation by the Pope that his marriage to Catherine had never been valid in the first place, on the grounds that he had married his dead brother’s wife, a practice forbidden by Scripture. He saw her failure to bear a male heir as God’s punishment for this sin. The Pope had granted annulments to other nobles on far flimsier pretexts. The reasons he would not hear Henry’s case were less than spiritual. Catherine’s nephew was the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and the Pope needed his continued support.

Cranmer was the man who would help Henry break from Rome. His motivations were different from his sire’s. Henry wanted only local independence, a Catholic church under his jurisdiction rather than that of the Pope. Cranmer wanted reform. His first Prayer Book of 1549 was a relatively conservative translation of the older Latin liturgies, trimming down the many books needed to offer divine service into one volume, easier to use and easier to propagate so as to enforce a single liturgy across the realm: a book of prayer “common” to the whole kingdom. The revisions of 1552 moved in a more Protestant direction, but it barely had time to cool from the press before Queen Mary abolished it the next year. Queen Elizabeth’s 1559 edition moved slightly back in the older direction and offered a bare-bones liturgical order which could be dressed as fleshily or sparsely as one’s ecclesiastical proclivities required. There were those who used it as a strictly spoken office book, without music or vesture, in Calvinist style. These were not much pleased at how, in contrast, the Queen herself used it, as one such in 1560 despaired:

What can I hope, when three of our lately appointed bishops are to officiate at the Table of the Lord, one as priest, another as a deacon, and a third as subdeacon, before the image of the crucifix, or at least not far from it, with candles, and habited with the golden vestments of the papacy; and are thus to celebrate the Lord’s Supper without any sermon?

Battles continued between those who would enrich the Church’s liturgy, emphasising its continuity with ancient tradition, and those who wished to dispense with such tradition entirely. This was true not only in England. Archbishop Laud, serving under the High Church King Charles I, drew up the 1637 Scottish Prayer Book, restoring the older 1549 form of the Eucharist. The first attempt to use it in Edinburgh’s St Giles Cathedral resulted in a riot, with books being thrown at the priest, and the words of the market trader Jenny Geddes echoing to posterity:

“Daur ye say Mass in my lug?”

(Dare you say Mass in my ear?)

The book, among other causes, ecclesiastical and political, resulted in war and the decapitation of the King. Its more Catholic emphasis would, however, exercise a lasting influence on later international Prayer Books, among that that of the Japanese church.

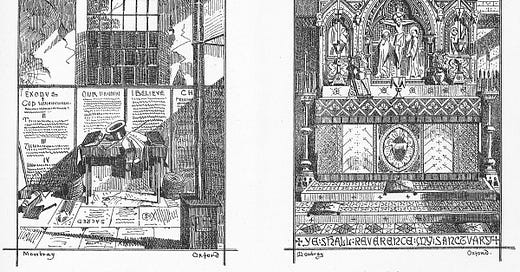

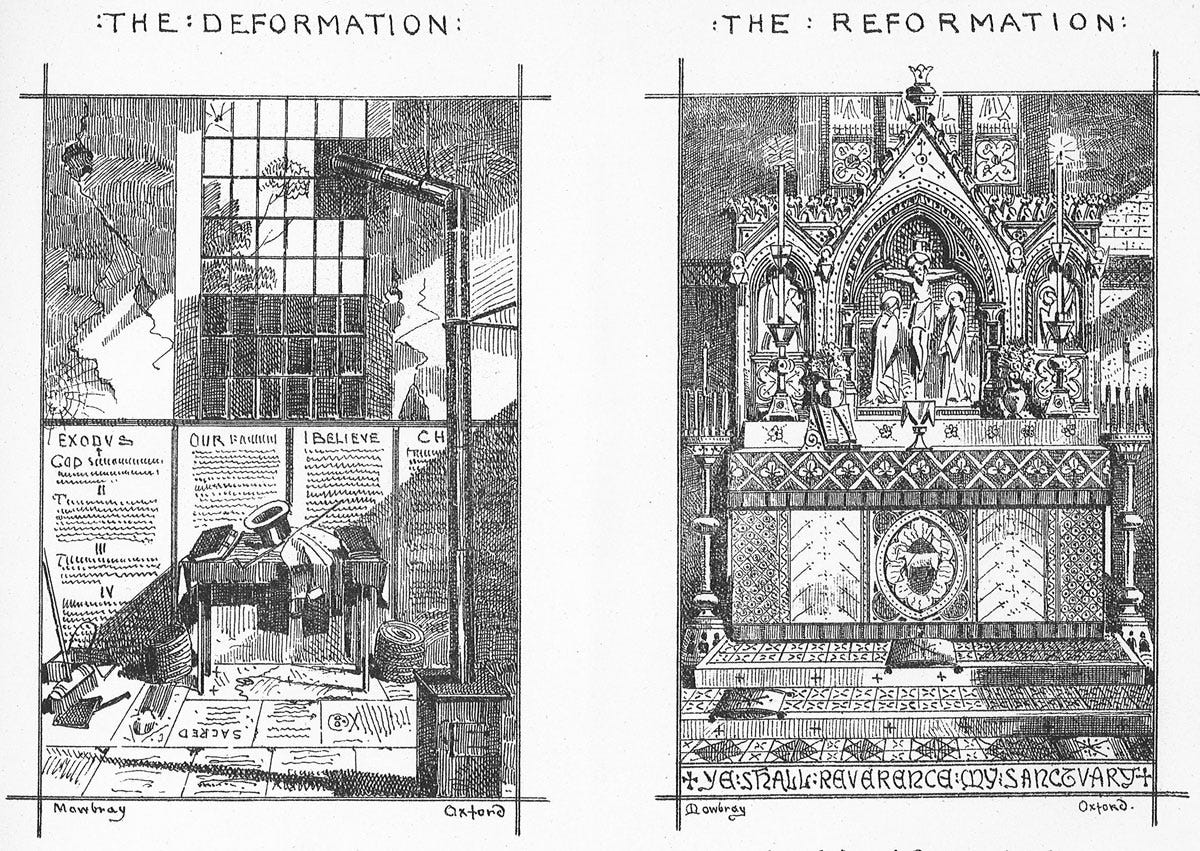

We return at last to Cromwell. He was overthrown and the monarchy happily restored, along with the deposed bishops and the deposed Prayer Book. In 1661, the new King Charles determined to hold a conference in Savoy to mediate between the bishops and the Puritans who had held sway in Cromwell’s time and so revise the Prayer Book. This is the pristine state to which the Puritans wanted to return:

Prayer, confession, thanksgiving, reading of the Scriptures, and the administration of the Sacraments in the plainest and simplest manner, were matter enough to furnish out a sufficient Liturgy, though nothing either of private opinion, or of church pomp, of garments, or prescribed gestures, of imagery, of musick, of matter concerning the dead, of many superfluities which creep into the Church under the name or order and decency, did interpose itself.

Note that they did not call any longer for the wholesale abandonment of liturgy, but regarded as unbiblical and undesirable much of what enriches it, including vesture, images and music. Even the sign of the Cross in baptism was deemed a “papalistic” superstition.

The Bishops retorted that the Puritans’ interpretation of the Reformation was flawed:

It was the wisdom of our Reformers to draw up such a Liturgy as neither Romanist nor Protestant could justly except against. … For preserving of the Churches’ peace we know no better or efficacious way than our set Liturgy … when the Liturgy was duly observed, we lived in peace; since that was laid aside there hath been as many modes and fashions of public worship as fancies. … If we do not observe that golden rule of the venerable Council of Nice, ‘Let ancient customs prevail,’ till reason plainly requires the contrary, we shall give offence to sober Christians by a causeless departure from Catholic usage…

The bishops prevailed and gave the Church the 1662 Book of Common Prayer still current in England today. Most, though not all, of the Puritans’ demands were rejected.

Over the next century, the Book which had been perceived as a radical and revolutionary departure from ancient practice now became the hallmark of the liturgical and Catholic-oriented conservative. Various services were added over the next century and a half, including the commemoration of the executed monarch as St Charles, King and Martyr; a memorial service of the Great Fire of London; and, in 1714, an order for the consecration of church buildings. None of these were typical of Puritan concerns. Though never formally abrogated by the Church or Parliament, these services gradually faded out of the Prayer Book at the whim of Victorian printers. However, it is in the Victorian age that the greatest liturgical renewal of the Church of England took place, with lasting consequences to this day.

I speak, of course, of the Oxford Movement, generally dated from 1833 and the priest John Keble’s Assize Sermon given at the University Church of St Mary, provocatively entitled "National Apostasy.” Since non-Anglicans had recently been permitted to become members of parliament, this meant that the doctrine of the established Church was being decided by people who were not its members, including some even hostile to it. Keble preached against this development, arguing that the Church’s true authority must rest not on Parliament but on the bishops, as legitimate successors of the Apostles. Inspired by Keble, fellow Oxford men John Henry Newman and Edward Bouverie Pusey began the scholarly work of defending the continuity of the Church of England with the wider Catholic Church. They unearthed the ancient liturgical sources behind the Prayer Book, demonstrating ingeniously, if sometimes a little tenuously, that they were not merely innovations, but were derived from and consistent with the practice of the ancient Church.

While the proponents of the Oxford Movement focussed mostly on reinterpreting the doctrine of the Prayer Book, the next generation saw the need to match their doctrinal interpretations with liturgical practice. Citing the Ornaments Rubric of the Elizabethan Prayer Book as justification — “such Ornaments of the Church, and of the Ministers thereof, at all Times of their Ministration, shall be retained, and be in use, as were in this Church of England, by the Authority of Parliament, in the Second Year of the Reign of King Edward the Sixth” — they reintroduced candles, incense, vestments, robed and surpliced choirs, altar plate and crosses, as well as enriching Anglican worship with new translations of ancient hymns to ancient melodies. The recovery of Merbecke’s setting for Holy Communion and much of today’s English hymnody comes from this period and those churchmen who would come to be called “Anglo-Catholic.”

These restorations of ancient liturgical practice, once enjoyed by Queen Elizabeth I, seem nowadays quintessentially Anglican and uncontroversial. In Victorian times they were exotic enough to stoke riots. 1844-5 saw the two-year Surplice Riots in Exeter, following the Bishop of that Diocese’s enforcement of the garment’s use by all clergy. In the 1860s, priests went to gaol for using wafer bread and having lighted candles on the altar. The situation was regularised only in 1906 with the Royal Commission on Ecclesiastic Discipline, which recommended further revision of the Prayer Book, hindered by the advent of the Great War of 1914-18. This threw Army chaplains into situations where the lengthy services of Common Prayer were unsuitable. Their voices added to the Anglo-Catholic party’s call for reservation of the Blessed Sacrament for distribution to the sick to be legalised, and for the offering of Requiem masses, thereby restoring the hitherto forbidden practice of prayer for the dead. Ironically, as Keble had forewarned almost a century before, these proposals were rejected by Parliament thanks to objections by non-Anglicans, to the bemusement of a young Winston Churchill who reported somewhat ironically on the proceedings. The proposed 1928 Book of Common Prayer was thus never universally authorised, though permission was given for its use by individual bishops within their dioceses, and the 1662 remains in legal force to this day.

6 Anglican Liturgy Today

The Anglican Communion is now far larger than the Church of England alone, and the liturgy of the mother church is no longer normative throughout the churches. The churches themselves are in schism, divided over the authority of Scripture, particularly regarding sexual ethics, which, we noted, were strictly stipulated as early as the Jerusalem Council of AD 49. The Church of England is now part of a minority communion. Some 80% of Anglicans, mostly in the Global South, are instead represented by the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON). In both communions, there is a general fault-line between conservative Evangelicals and liberals. Anglo-Catholics fall somewhat uncomfortably into both of these spheres. However, it is noteworthy that outside the Church of England and those parts of GAFCON influenced by the anti-liturgical Diocese of Sydney, Evangelicals are increasingly turning back to more conservative liturgical practice, taking the Book of Common Prayer as a touchstone of Anglican practice and identity. Incense is not found much outside Anglo-Catholic churches, but it is no longer the case that vestments, candles, crosses, choirs and organs indicate a particular church party: there are Evangelical churches, such as those of Singapore, in which all of these are used. Parts of the non-Anglican Reformed world are also embracing the Prayer Book and its liturgy. Conversely, nor are more modern musical settings, hymns and songs restricted to the Evangelical world, and guitar-driven worship bands can be found in the midst of ritualistic High Masses. Beyond England, we are seeing something of a synthesis between Anglo-Catholic ritual practice and the Evangelical emphasis on Scripture.

Some have prophesied the demise of the Oxford Movement within our lifetime, and there is no doubt that it has declined considerably in recent decades. This may be premature. The liturgical influence of the Oxford Movement lives on, albeit in surprising places, and the Prayer Book continues to inspire new generations with zeal for God and a clear rule of life to guide them towards His grace.

Fr Thomas Plant

https://substack.com/@frthomasplant

If you would like to support Fr Plant, you can purchase his The Prayer Book Society Teen Guide to the Book of Common Prayer: