Lent 2 – Year B, Revised Common Lectionary

Texts: Gen. 17:1-7, 15-16 | Romans 4:13-25 | Mark 8:31-38 | Ps 22:22-30

Collect:

Almighty God, you know that we have no power in ourselves to help ourselves: Keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls, that we may be defended from all adversities that may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts that may assault and hurt the soul; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

The Uncertain Present

Introduction

We are in the second Sunday of Lent, and in this season let us remember that the reason for Lent is to prepare for the coming Easter feast. As we fast, we do so not to deny things that are good, but instead exercise our spiritual muscles. When we exercise, we tend to do so with the future in mind: someone going to the gym to get in shape goes not expecting the present experience to be 'in shape' but how the exercise will eventually change them. Our Gospel Lesson today presents a similar paradigm.

At this point in the Gospel Jesus has already fed the four thousand, and healed the sick and the blind. He asks Peter who do people say that he is. The disciples offer a few thoughts; Peter nails it: "you are the Christ" And Jesus responds with, "Shh! Don't tell anyone." By all accounts everyone is bringing in what they think the Messiah should be: a man with Solomonic wisdom, Prophetic signs and wonders, and the all-around Kingly prowess of David; that is, the passion, military might, and a revolutionary attitude which honors God.

This is an immense diversity of expectations placed on Jesus, and so he offers his followers an even bigger picture: he will not win victories against the government—Jewish and Roman—but instead be rejected as “not the Christ” (though he just affirmed that “he is the Christ”). Instead of the praise of a King, he would be disavowed and discarded. Instead of establishing a world power, he would instead be crushed under the weight of torture and crucifixion. But most perplexingly, he says, plainly, that he will rise again three days after.

Peter does not like this. At all. Peter is passionate, and wants to make things happen. Peter wants none of this: none of the rejection, none of the death, and whatever is meant by three days later… Well, none of that either.

Jesus, rightly, rebukes Peter for this, as the cross is a necessary step in redemptive history that must take place if the world is to be brought into glory, that is, the true beauty of the presence of God. This was in the redemptive plan of God god carried through from the aftermath of the Fall, to Abraham, to Moses, to David, to Jesus.

We tend to get stuck on the "get behind me Satan" bit, but I want to draw your attention to the explanation that follows: "For you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man"

"For you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man"

Peter had a very human future in mind, and in his interest, he forgot where Jesus might be bringing them. Peter gets a bad rap, but, hypothetically, consider this: A single man just fed four thousand followers from a few small rations of bread and fish. The same man just healed a blind man. The same man is probably the Messiah. (So far so good.) Now this man just said he is going to be rejected in spite of these signs, and killed in the most painful, shameful way possible. And even more puzzlingly, he also claims that he will then return from the dead. This would be very upsetting, particularly if you had your own aspirations in a political upheaval that could bring about a regime change against the Romans, with this Jesus of Nazareth at the helm.

But these were all plans of Peter for what he wanted out of the Future, when Jesus just told him the future. I think Peter became very uncomfortable with Jesus’ plan, because it didn't fit his idea of where this was headed.

Some years ago I read a very difficult book by a former Nashotah House professor, Arthur Vogel, called Body Theology. I think it took me six months of coffee-shop reading to finally break through it. In it Vogel mentions that most of our anxieties are related to attempting to hold on to the present. If we are physically suffering, we are not anxious in the same way. But the anxiety that is systemic to our culture–that is, at its foundation–is based on attempting to hold on to the present. This, he argues, is because the future is uncertain: we want to hold on to what we have, because we don't know if it will last, or if the future will be worse. And in the end, we die.

This is about as far from Christian Living as one can get. The Christian life, Vogel says, is a life lived with full trust in a certain future: That Christ is coming again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead, whose Kingdom shall have no end, and we can look forward to this great resurrection from the dead, and the life of the world to come. This is a certain future.

Think of it this way: If the future is a promise of God, which he is still active in fulfilling, the present exists by nature as a transition from the past to the future. The present is never static. A Christian life differs from an anxious life by this: since the future is certain, the present can always be expected to change, and be received with joy. The anxious life has no certain future, and so must try to keep the present as long as possible. Change is something we can always anticipate. Jesus rebukes Peter's rebuke, because there is a bigger promise to fulfill—a more important future—than Peter's present.

To this end, Jesus gives three instructions:

1. Deny yourself

This is not, as many practice in Lent, a self-flagellation. Rather it is rejecting self-consciousness, which produces anxiety. Ask yourself:

Who are you?

When do you feel most yourself?

When do you truly feel like you are living?

Is it when you are thinking about yourself?

Or is it when you lose yourself in something, or time with someone?

To be truly present with someone is to not be fully conscious of our selves: we are in the moment that is always moving. Our favorite memories are almost always the ones we weren't conscious of when they were being made: we were too busy in the moving of time to notice the moments we in retrospect cherish.

It was those little sequences of 'the present' that made us who we are now. To hold on to each moment, like a photograph, or social media posting, selfies, and so on, is to take our experience out of the moment, and distance ourselves from the relationship.

If we can accept the promises of God, that he has a future for us, then the changes of the present are not things to be resisted, but accepted as what they are: They are the process of us becoming who God wants us to be. But this is not easy.

2. Jesus says take up your cross and follow me.

He never calls us to that which he cannot understand, and though the disciples at this point do not know it, Jesus is first among them to do so: he took up the cross and was obedient to the plans of God. But in so doing brought about salvation to the world, the effects of which are continually unfolding.

The spiritual life of a Christian is not to avoid suffering, but to give meaning in suffering. Just as we cannot hold on to the present, we can not avoid the valleys that come our way: to live only on all peaks means we've actually plateaued. Indeed, it is through our suffering that we often experience the greatest growth, which we only appreciate in hindsight, where at the end we looking back on this life from Glory, with gratitude.

What, then, can lead us through present hardship? Knowing, trusting that God has a future in mind for us. Paul reminds us: "For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us." (Romans 8:18)

3. Jesus says Follow Me

Here Jesus offers us a paradox: follow him, because that is the only way in which we get what we really want. It is the answer to the question: What are you fighting to hold on to? We were bought with a price, and as such, we do not own ourselves, nor anything that we seek to retain: we are God's, and he cares for us more than we could ever care for ourselves. If we care for ourselves, we become anxious; but if we let God care for us, we have peace.

We know that are loved by God, because of what Christ has done for us. Paul expands late in his letter to the Romans: "For none of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself. For if we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord. So then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord's. For to this end Christ died and lived again, that he might be Lord both of the dead and of the living." (Romans 14:7-9)

There is an anonymous prayer, commonly called the prayer of St. Francis which embraces the paradox that Christ presents us:

Lord, make me an instrument of Thy peace;

where there is hatred let me sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

and where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master,

grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled, as to console;

to be understood, as to understand;

to be loved, as to love;

for it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

In order to become what you want to be, lose the present and take heart that all change that comes will be used of God to bring about his promises for your life, which is resurrected glory, which began on the cross 2000 years ago. However, if you wish to hold on to everything you have in the present, you will lose the future.

All of this boils down to trust in God's promises, which is faith. Bishop Vogel summarizes what it means to trust : "To trust in God is to welcome anything that can happen to us in the world. That is what it means to be in the world but not of it." (Body Theology, p.82)

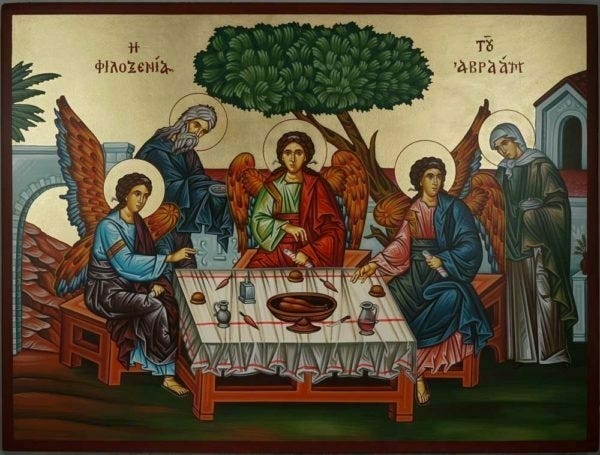

Faith, as Abraham is so honored in our lessons, is trust: Do you trust in God's promises for a future: one of good and not of evil? Abraham did, and that faith was counted as Righteousness, "for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose." (Rom 8:28).

And the present is just that: a continual gift of God that is, step by step, in happiness and hardship, bringing you to what you are going to be: one who can truly enjoy that divinely ordained future kingdom.