A Case for the 1662 Book of Common Prayer

Why use the 1662 or 1662:International Edition? Answering from the perspective of Anglican identity and mission.

{Part of a series}

(This essay was subsequently cross-posted on The North American Anglican)

I was chatting with a priest-friend about the 1662: International Edition of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), and he playfully remarked to me that I must be the only Anglo-Catholic priest in America that likes the 1662IE. He classified it as having mostly a Reformed-Calvinist following. I don’t think this is necessarily the case, but it occurred to me that I should write out some of my reasons for supporting it—or more broadly the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

The International Edition of the 1662 BCP was commissioned by the Prayer Book Society USA to be a book to succeed the 1928 BCP,1 since both ACNA and TEC have not retained key elements of the classical Prayer Book tradition. While the former’s 2019 is a conservative revision of the 1979 book, the 1979 was the starting text from which revisions were made, not the classical 1928/1662 tradition. Indeed, neither ACNA nor TEC retain many classical Anglican elements in their prayer books, regardless of Traditional or modern language. Most prominently, this is found in the 1979-influenced collects and the modern 3-year lectionary brought about by 20th Century Liturgical Movement.

The 1928 BCP, used by (tens of) thousands worldwide in the Continuing Movement; and the 1662, used by millions worldwide in the Anglican Communion/Gafcon, are among the few “uses” preserving the ancient lections of the Western Tradition.

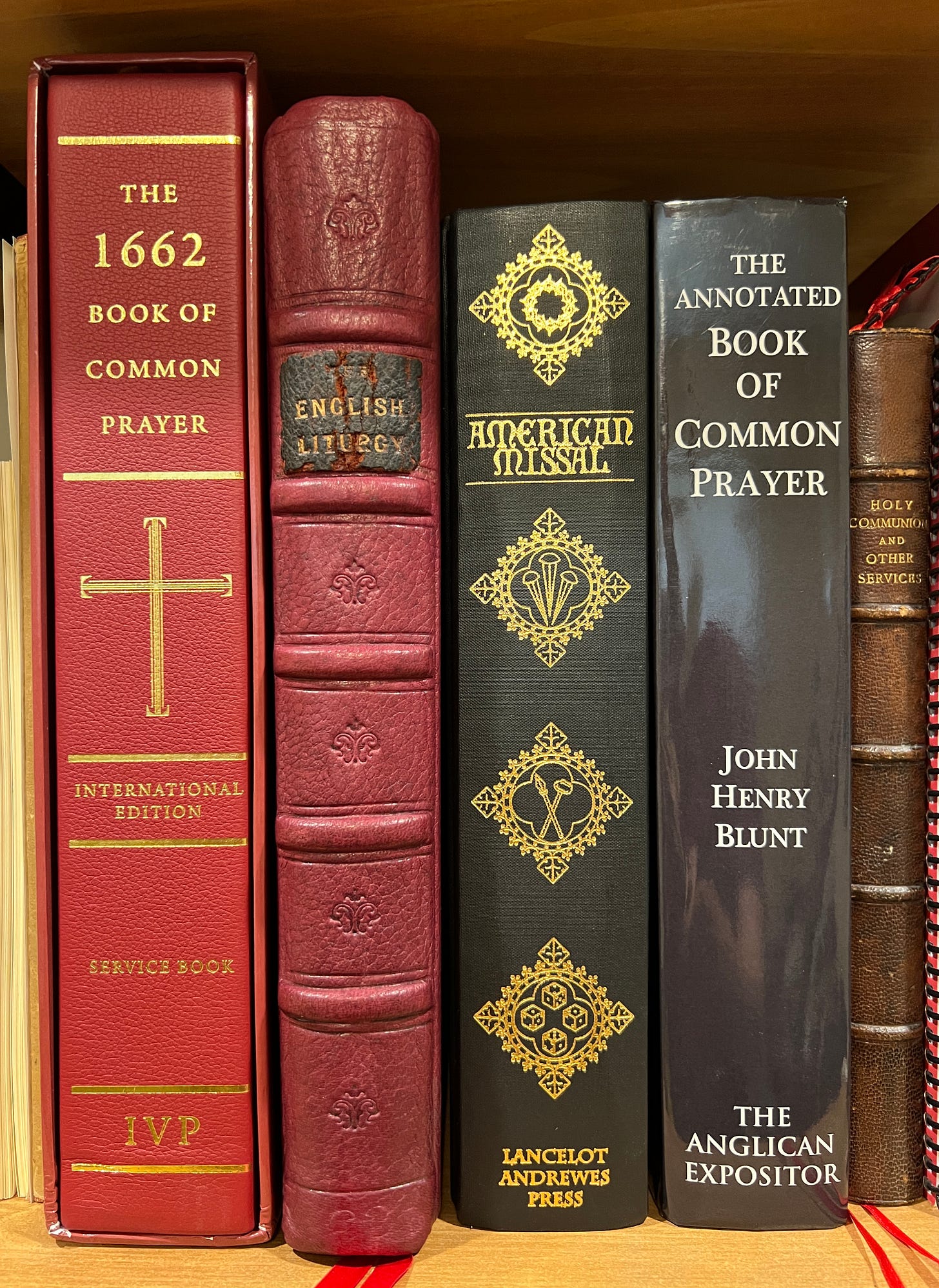

The 1662:IE makes adjustments for those not in the Commonwealth, as well an appendix (III) allowing for pointers as to how the book has been used over the centuries. It includes a glossary and an abundance of additional prayers that exceed those of 1928 and harmonize with 2019. With these, I have found it exceeds the practical usefulness of the American 1928 BCP. That said, the 1928 has a greater variety of Canticles and a more Lancelot Andrewes-infused Holy Communion service order.2

But the larger question: Why the 1662? Personally, it is not because of stylistic or aesthetic preference; rather, it is a book that for me solved a recurring question of Anglican Identity amidst the cacophony of “Anglicanisms.”

Anglican Identity

The Rev. Canon Robert Bader, a priest in the Diocese of the Holy Cross, now part of the Anglican Catholic Church succinctly writes:

“It is my contention that there are essentially three types of Anglicanism in the world today […] Canterbury Anglicanism, GAFCON Anglicanism, and [Affirmation of St Louis] Anglicanism.

[…]

Canterbury Anglicanism needs little explanation. It is the prevailing ideology in the Church of England, the Episcopal Church, other First World Anglican provinces, and some Third World Anglican provinces. […] Many of its adherents maintain aspects of Evangelicalism or Catholicism, with the glaring exceptions noted. But it is fundamentally open to revisionism on any issue of faith and morals.[…]

GAFCON Anglicanism is the ideology associated with the Global Anglican Future Conference, the 2008 meeting of bishops from mostly Third World Anglican provinces, which was instrumental in the creation of the currently named Anglican Church in North America (ACNA).

[…]

[St. Louis Anglicanism] is the ideology set forth in the Declaration of Scranton and the Affirmation of St Louis […] St. Louis Anglicanism is what N.P. Williams described in Northern Catholicism: “Catholicism which is neither Roman nor Byzantine; which is non-Papal, but at the same time specifically Western in its outlook and temper.”3

In terms of spirituality (lived theology; not ecclesiastical authority), these are overlapping Venn-circles, though the latter overlaps least because of its earlier self-separation from the larger body. In Canterbury Anglicanism, there remain those who might be better defined as St Louis Anglicanism in terms of belief and spirituality. In ACNA/Gafcon, there are churches and dioceses that are in many respects more in-step with the Episcopal Church (Canterbury) on many issues, yet there are churches that also would align more strongly with St Louis Anglicanism.4 And some St Louis Anglican churches are more Protestant Episcopalian than non-Papal Catholic.

The state of Anglicanism over the last 50 years was born out of a sort of divorce, first begun in the 1970s, continued globally in 1992, both over the ordination of women to the priesthood; and again breaking in 2003-2009 over the issue of human sexuality.

In the ACNA, because of very real differences over first-order issues, some dioceses are not universally conferring valid sacraments,5 nor do all dioceses exist in full communion with one another.6 The question looms whether 20th century changes to the church are those which are catholic: if the authority of the church is rendered doubtful over legislated heresy ,7 then how should one feel about other aspects of the last 50 years that are shaping Anglican identity, such as prayer book liturgy, worship, doctrine?

For those new to “Anglicanism,” one might be surprised that a very diverse group of people claim to be Anglican, often in contradiction with one another.

One question an inquirer might ask is, “how much does a particular ‘Anglicanism’ participate in what could be called The Anglican Tradition?”

Or , “how much does an interpretation of the Tradition maintain the Catholic deposit of faith?” — a deposit that, many argue, providentially survived the Medieval, Reformation, Anglican Counter-Reformation,8 and Restoration, at great cost to many godly bishops and the martyrdom of a monarch, St Charles, King and Martyr?

It is true that each century has had factions that hold particular characteristics of their shibboleth, whether it be the High Church versus Low Church, Oxford Movement versus the Latitudinarians, Evangelicals versus the Ritualists, and so on. And in the 20th Century, many of these categories shifted into social/moral categories rather than modes of worship, some of which brought about by liturgical change. But there is a core to which we can all look to “hold the center” of the tradition.

I submit that living within the foundation9 of the 1662 BCP best prepares one to pray and worship10 within the center of such a venn-overlap: to exist within the best of Canterbury, Gafcon, and St Louis Anglicanisms.

Why the 1662 Book of Common Prayer?

Before I was Anglican, I was mentored by a godly priest in the Eastern Orthodox church. What I saw among fellow inquirers was a desire for confidence (i.e., validity) in apostolic sacraments, worshipping in historic consistency (stability), alongside and in a like manner to an expanse of fellow Christians, past and present (global). In other words, to be within the broadly Catholic tradition (cf., Vincentian Canon ‘by all, always, everywhere’). The 1662BCP represents well the English use of the same.

It has provided me the answer to the question: “How can one be faithfully Catholic within the Anglican Tradition—insofar as prayer, liturgy, and spiritual formation—without diverting to provincialism?”

It is Catholic in Sacrament.

While the 1662 in America seems to have following of those who would be more Reformed-Calvinist, or what the continuum has called “Canonical Century,”11

there is no reason for Anglo-Catholics to avoid the 1662’s ancient catholicity because of divergent theology of other proponents. That their fight for the 1662 is rooted in a historical narrative hostile to Anglo-Catholics is not the book’s fault.

The 1662 is largely the same book that the Caroline Divines used, who being Reformed, were nevertheless not “Presbyterians with Prayer Books.” This is also so with the Tractarians and 19th Century Ritualists that produced the Anglo-Catholic movement. The Prayer Book used by Pusey, Neale, Keble, was the 1662. So too with Maurice, Lowder, Dearmer. When a Tractarian, Newman even wrote a case for keeping the 1662 as it is. 12

There are likely few American Anglo-Catholics who use 1662, but it may be of interest as an alternative to 2019 TLE or the 1928, following the example of the Prayer Book Society UK,13, and the Diocese of Oswestry, Bishop Paul Thomas, SSC to celebrate the 1662 BCP as a fully Catholic liturgy, and support its use.14

The 1662 may have some deficiencies, but as many have noted, such may be supplemented with additional devotions, as SSC has supported15 and SSJE’s Palmer and Hawkes outline.16

The 1662 represents a providential aspect of Anglicanism: it is the distilled minimum liturgy, following the spirit of the Reformation. While one should be wary to remove material from a minimum, it may be right to augment—restore—prayers, ceremonies, and devotions which may not carry the same “Romish” connotations now. This is especially helpful in recovering ancient traditions of the church, largely purged from consciousness during the canonical century, dimly remembered in some quarters in succeeding years, but rejected in few quarters today, thanks the Oxford Movement and those spiritual children the movement birthed. Indeed, the Roman Catholic Ordinariate issued a Commonwealth Daily Office Breviary that is more or less the 1662 with additional devotions, including the same 1961 Lectionary the International Edition includes.

It is stable in history.

It is important to note that the 1662:IE is popular especially to those outside the Anglican world, proving its own inherent appeal to those interested in prayer and spiritual formation within the Anglican tradition. This interest is not what was written as revolution in 1979, or reaction to the same in 2019, but a tradition approaching 400 years of use. While few would say it is a perfect book,17 it has proven the test of time, much as the King James Version of the Bible has.

The 1662 remains a foundation for most of Anglicanism, both in the history of the Anglican tradition and in millions of adherents today.

The late Fr Peter Toon (Prayer Book Society USA president) noted in 2007:

“The use of The BCP 1662 as the standard text and base line seems to be a real possibility for a large sector of would-be orthodox American Anglicanism and through it may come the restoration of the authentic Anglican Way as Reformed Catholicism and part of a global Family. For parishes with a solid musical tradition, the use of The BCP 1662 opens up massive possibilities of classic and modern sung services and of course with this Prayer Book comes a tremendous devotional and theological literature, together with marvelous poetry and special services (Advent Carol Service etc.). Not least with this tradition comes the missionary zeal, exhibited in the past by the major evangelical missionary societies of England—e.g., Church Missionary Society.”

Since then, this has been largely true, within the ACNA, Gafcon, and the orthodox few in the See of Oswestry (part of Forward in Faith UK). The 1662, even if not fully utilized, remains a standard for faithful, orthodox Anglicans worldwide in a way no other single prayer book has achieved. This represents nearly four centuries of stability in prayer, liturgy/worship, sacraments, and prioritization of scripture.

This foundation, I believe, is compelling in a way that provides a missionary narrative for the Anglican Tradition in a way that emphasizes our identity, without looking to Presbyterians, Eastern Orthodox, or Roman Catholics, but respecting each. It means that we have out own history, as the Byzantines do: the 1662 as a base text provides us western roots to the ancient, patristic church in ways that is often lack in many Roman parishes, as well Anglican parishes that follow the 20th/21st century zeitgeist revisions.18 Stability is part of what attracts converts to Orthodoxy and Rome, and lack of stability—being recent social-doctrinal developments exemplified in liturgical revision—what repels people from contemporary Anglicanism.

I contend that, of the multitude of Anglican-adjacent jurisdictions (Anglican Communion, Gafcon, St Louis Continuing, Western Rite, Ordinariate), the 1662 represents a historic cohesive core to the tradition that retains a personal traditional Catholic Anglican identity—which is to say, a Benedictine-influcenced pattern of spiritual formation, prayer, and participation in sacraments—irrespective of a particular diocese, jurisdiction, or movement of culture. In its stability (including the Ordinal), it assures catholicity amid a myriad of changes and revisions of what is now called “Anglicanism.”

It is global in use.

The 1662 is not just a book for England, or the Commonwealth. It is a book used in 50 countries, 150 languages, and one using it can confidently worship in continuity not just with many hundreds of years of saints before us, but also those around the world presently:

1662 in English Anglo-Catholicism

Bishop of Oswestry has reorganized and revivified a tired and demoralized See, which lost its last bishop to Rome, and has become a beacon for traditionalist Anglicans in England and abroad. Oswestry aims for what he calls “total evangelization,” driving hundreds of miles weekly to lead his people and pastors in prayer and catechesis. He brooks no “fakery,” and while he may have the voice and vesture to rival anything on in the West End, he is no pantomime dame.

What is more, unusually among Anglo-Catholic bishops in England, Oswestry is an ardent supporter of the quintessentially Anglican liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer.

[…]

The Prayer Book Society [UK], under His Majesty’s patronage, is enjoying a consistently larger and younger membership every year. It encompasses conservative Evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics, as well as some “Broad Church” latitudinarians and liberals from both ends of the churchmanship spectrum.19

1662 in Gafcon

“Gafcon is a global movement within the [Anglican} Communion which represents the majority of all Anglicans.”

From Gafcon’s 2008 Jerusalem Statement:

We rejoice in our Anglican sacramental and liturgical heritage as an expression of the gospel, and we uphold the 1662 Book of Common Prayer as a true and authoritative standard of worship and prayer, to be translated and locally adapted for each culture.20

1662 in the Traditional Anglican Communion (Affirmation of St Louis)

The 1990 Traditional Anglican Concordat of 2003:

This Communion retains and approves the formularies of the classical Anglican tradition authorized prior to the emergence, within some Churches or Provinces of 'The Anglican Communion,' of those departures from orthodox Faith and Practice which made necessary and precipitated the Congress of St. Louis. The standard of Faith and Worship of this Communion is that expressed in the first Book of Common Prayer, and Ordinal, of Edward VI and in the following revisions: [1662, 1962, 1928, 1963, 1926, 1954, and The Church of England Deposited Book of 1928]21

The Anglican Catholic Church, which is not part of the Concordat, authorizes the American 1928, English 1549, South Africa 1954, Canadian 1962, India 1963 Books of Common Prayer; the last of which contains the 1662 Holy Communion liturgy.22

1662 in ACNA

The ACNA, including the REC and those in Forward in Faith, support as a provincial foundation the 1662 BCP, from Fundamental Declarations of the Province (contained in the Constitution of the Province):

We receive The Book of Common Prayer as set forth by the Church of England in 1662, together with the Ordinal attached to the same, as a standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline, and, with the Books which preceded it, as the standard for the Anglican tradition of worship.

Why not use the standard?

While I am not advocating that 1662 be used in all cases, in all places, I hope that advocating for it, and producing materials to encourage the accessibility of it—especially including the 2019:TLE with 1662 Service Order—will help the mission of the church where it is expedient: to make disciples and preach the good news; and to worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness.

///

See Dom Benedict Andersen, The Caroline Liturgical Movement

For example, the Missionary Diocese of All Saints, for example, which had contemplated leaving in favor of the Union of Scranton, yet chose to remain as a Catholic non-geographic diocese (functionally, a Forward in Faith subjurisdiction) within the ACNA.

We recognize that baptism is a sacrament that can be administered by a layperson. But the consecration of the Holy Eucharist requires a validly ordained priest. The practical problem of the ordination of women is that we have some churches and altars where this sacrament of the Supper of the Lord is not recognized as true and valid throughout the province, bringing up the question: Can we even consider ourselves a church, by definition, as long as this is the case?

— 2024 Diocese of Forth Worth Standing Committee

“We are in a state of impaired communion because of this issue. The Task Force concluded that ‘both sides cannot be right.’ … it is no longer possible to have ‘business as usual’ in the College of Bishops due to the refusal of those who are in favor of women priests to at least adopt a moratorium on this divisive practice, for the sake of unity.”

– Bishop Jack Iker, 2017 annual diocesan convention address

We affirm that these are first order issues in the Church, affecting the validity of sacraments and the grace that is (or is not) bestowed in such rituals …. The Church never has, does not now, nor ever will have the authority to change any doctrine whatsoever. These are truths revealed from heaven. As mother and teacher of the faithful, the Church’s only role is to define, explain, and proclaim doctrines as divine revelation from God. And she should always seek to conform her pastoral practice to the truth of doctrine.

– December 19, 2023 Diocese of Forth Worth Standing Committee

Foundation does not mean the only place to which one looks. All traditions —Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, Evangelical—practice personal supplementation to their spirituality, even if for some it is reading mostly Lewis. There are excellent resources to which one could complement the 1662: St Augustine’s Prayer Book, on the catholic side; Every Moment Holy or My Utmost for His Highest for the modern the Evangelical.

Additionally, there are annotated prayer books, as well as occasional services and customs not found in the prayer book or canons to be found across all churchmanships: Anglo-Catholic, High Church, Low Church, etc.

Homo adorans: humans as worshippers

“those I tend to describe as canonical-century fundamentalists — those who see Anglican identity as completely and exclusively defined by the years 1552-1662.”

— Fr Mark Perkins, https://www.earthaltar.org/post/six-theses-on-anglican-identity

Thoughts Respectfully Addressed to the Clergy On Alterations in the Liturgy, Tract III, Tracts for the Times

There are some who wish the Services shortened; there are others who think we should have far more Services, and more frequent attendance at public worship than we have.

How few would be pleased by any given alterations; and how many pained!

But once begin altering, and there will be no reason or justice in stopping, till the criticisms of all parties are satisfied. Thus, will not the Liturgy be in the evil case described in the well-known story, of the picture subjected by the artist to the observations of passers-by? And, even to speak at present of comparatively immaterial alterations, I mean such as do not infringe upon the doctrines of the Prayer Book, will not it even with these be a changed book, and will not that new book be for certain an inconsistent one, the alterations being made, not on principle, but upon chance objections urged from various quarters?

Bishop Paul Thomas, demonstrating his parish’s use of the 1662 for the Prayer Book Society UK, with narration:

Bishop Thomas has written an excellent book on the use of the 1662: Using the Book of Common Prayer: A simple guide.

“The same principle also was applied to modes of worship. It followed that it could not be wrong, especially if the local rite gave no explicit directions, to look to the living rite of Western Christendom as an authority for guidance in matters of ceremonial and devotion. We have become accustomed of late years to hear much, for divers reasons, of omissions in the Prayer Book and its need of "enrichment." S.S.C., always in advance of its age, had realised long before, that the Prayer Book was not a complete Directory of Public Worship and was never intended to be final. For making good many of the omissions, both of ceremonies and of prayers, there was ample precedent, even in the days of the strictest pressure for uniformity. Archbishop Grindal, when at York, had complained of "Popish customs then prevalent" and of the clergy following ceremonial that was not in Elizabeth's Prayer Book. The Baptismal rites, the pauses and intermissions in reading the services, the Candlemas Day ceremonies and other practices, were "as amongst the Papists." In 1685, a clergyman named Sparkes was prosecuted in the Court of King's Bench for using "other prayers in the Church and in other manner "than those provided in the Prayer Book. He was acquitted on the ground that he had used "other forms and prayers" not instead of those enjoined, but in addition to them. S.S.C. therefore was introducing no innovation when it turned its eyes elsewhere for guidance in those matters which the Prayer Book omitted, but nowhere prohibited. And where more fittingly could it turn its eyes than to the prevailing Western Rite?” – The Catholic Movement and the Society of the Holy Cross, by J. Embry (1931)

My own preferred Book of Common Prayer is the Lancelot Andrewes Press Book of Common Prayer, containing the Eastern Othodox Westetn Rite Liturgy of St Tihkon. But it is the catholic, historic, stable, global nature of the 1662 BCP that compels me to support it.

Fr Thomas Plant, in The King’s Letter:

“What draws people to the Prayer Book is what drew King Charles to the Orthodox Church: great, timeless tradition, uncorrupted by the vagaries of political correctness. It offers stability, a basically unchanging repository of Scripture and Apostolic tradition. Applied as it is written, even the English book of 1662 offers a Kalendar of feasts and fasts, a daily pattern of offices in the finest English verse and prose, thrice weekly Litany after Mattins, provision for Holy Communion every Sunday and saint’s day, and the possibility of private penance. These are not arbitrarily invented, but inherited and translated from ancient sources. The rubrics leave it open to a range of musical settings including ancient chant, and it can legitimately be enriched with traditional use of vestments and incense, without being limited to the late-nineteenth century conventions stipulated in Rome (the unified system of “traditional” liturgical colours are in fact something of an innovation), and without jettisoning the ancient lectionary of the Western Church (freely usable in the Church of England through the BCP, but only under sufferance of the local bishop through the Tridentine rite in Rome). Those of a more Catholic mind might complain, legitimately, that the 1662 Prayer Book lacks invocation of the Saints and prayer for the dead, but many churches of the Anglican communion have reintroduced these in the last century or so as permissible supplements to the liturgy. The Prayer Book tradition broadly construed, rather than the “Prayer Book fundamentalism” of sticking rigidly to every letter of 1662, offers the possibility of celebrating the holy mysteries in concord with the tradition the King so rightly admires.”

This 1662IE Missal Supplement represents one small effort at supporting this Prayer Book Catholicism, yet not Prayer Book Fundamentalism.