(Some years ago, I was moving away to a bi-vocational curacy at a traditional Prayer Book mission and the priest of the continuing parish I was attending offered me a pile of old pamphlets, as well a chaplain’s portable altar and a number of extra ‘church planting’ materials. As time and inclination lead, I plan to post some of these old mid-century pamphlets, occasionally with light edits. Hopefully minimal typos in the transfer. The only changes to the below pamphlet is to footnote the 1662IE page numbers when American 1928 BCP pages are referenced, and taking out a poem which will be posted separately. Since 1979 and 2019 BCPs are not in the same classical Prayer Book lineage, pages, quotes, references do not transfer quite as easily as 1928 <–> 1662[IE]. – ιμκ☩)

WHAT IS A "PRAYER BOOK" PARISH?

December 4, 1949

Every so often, in the classified column of THE LIVING CHURCH, a congregation wanting a rector describes itself as a “Prayer Book" parish, or indicates that a "Prayer Book" Churchman is desired. One of the questions that might well engage our attention, as this jubilee year of the Book of Common Prayer draws to its close, is this: just what is a “Prayer Book” Churchman? And what are the marks of a "Prayer Book" parish?

In attempting to answer these questions, we shall use the Prayer Book itself as a standard, looking as objectively as possible at that venerable authority. With a meticulous observance of ceremonial detail, with a slavish and almost fundamentalist interpretation o f rubrics, we are not here concerned. Our object is rather to present the elements of a well-rounded Prayer Book religion, in both its corporate and personal aspects.

CENTRALITY OF THE EUCHARIST

In a Prayer Book parish the Holy Eucharist will in every way be the principal act of worship every Sunday. As the principal act of worship, it will be held at that hour at which the bulk of the people attend. If the majority of the parish come at 11 o'clock, then the Eucharist will be celebrated every Lord's Day at that time. It will be the high water mark of Sunday worship.

As the center of parish worship every Lord's Day, the Eucharist will be given the music, if only one service can have it. If more than one service is musically rendered, then the best music will go into the Eucharist. That all of this is the intention of the Prayer Book should be crystal clear to anyone who approaches the matter without bias. For it is the simple truth that the Eucharist is the only service for which the Prayer Book orders a sermon, the reading of notices, and an offering of money. The obvious assumption is that this, wherever humanly possible is to be the parish gathering of every Lord's Day.

MORNING AND EVENING PRAYER

This does not mean that the Orders for Daily Morning and Evening Prayer are unimportant. As their very name indicates, these are daily services: on Sundays they should be said in addition to the Eucharist—at least by the clergy, preferably by clergy and people. Around the Lord's own service are meant to revolve — like satellites — Morning Prayer as an introduction, Evening Prayer as a thanksgiving. The point to remember is that these offices should be kept in a position subordinate to that action which, for 16 centuries from the Apostles' time, was everywhere throughout Christendom on every Lord's Day given central place.

The Prayer Book provides two cycles of scripture readings: the "Epistles, and Gospels to be used throughout the Year" — printed in full, because they are to be read at the largest gathring; and the Lessons for Daily Morning and Evening Prayer — given in a table and requiring a Bible with Apocrypha. Both of these are meant to be followed, wherever possible, with impeccable regularity, the Morning and Evening Prayer lections furnishing interesting, side lights on the primary Eucharistic scriptures.

HOLY DAYS AND FASTING DAYS

Then shall be declared unto the People what Days, or Fasting Days, are in the week following to be observed. . . . So says the Prayer Book, at the place for making the announcements, which follows the Creed in the Holy Communion (page 71).1 "Holy Days" — these are given on pages xIvi to xlix2 They are mostly saints' days coming during the week and averaging about two a month. The Prayer Book tells us that they are "to be observed." How? Obviously in the way that Sundays are kept: by using the Collect, Epistles, and Gospels provided for these days on pages 226 to 257.3 In other words they are "to b e observed" by a celebration of the Holy Communion. But by age-long precedent a priest is forbidden to offer up the Holy Eucharist without a congregation —without at the very least one other person present.

A Prayer Book parish, therefore, would be one in which the rector could count upon a congregation on all Prayer Book holy days — regardless of the day of the week or time of year. Conversely, a priest who is a Prayer Book Churchman is one who would be disappointed if he were unable, for want of another person present, to celebrate on a holy day for which the Prayer Book provides.

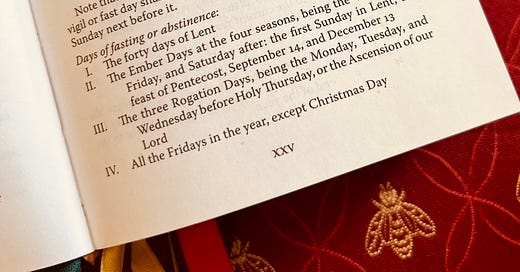

The same rubric mentions fasting days. These are outlined on page li4. They include the greater fasts of Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. Yet in the so-called Prayer Book parishes, how many of the people undertake on these days anything remotely resembling fasting? Below Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are listed other days of fasting, on which the Church requires such a measure of abstinence as is more especially suited to extraordinary acts and exercises of devotion. Included under these are "All the Fridays in the Year, except Christmas Day, and The Epiphany, or any Friday which may intervene between these Feasts."

This table, in substance, has been in the English Prayer Book from at least 1661, and was thence carried over into our [1928] American Book of Common Prayer. In the 16th and 17th centuries, “abstinence" meant going without meat, and everybody knew that the "days of abstinence" were those days upon which you "abstained" from flesh meat, whether you ate fish, eggs, vegetables, or something else. Everybody knew that; and the table merely said in effect: "Whatever days have heretofore been meatless days, the following are from now on to be observed as such." Yet in how many Prayer Book parishes are these days generally kept — by the bulk of the people? By members of vestries and their families? By the clergy?

SACRAMENTAL CONFESSION

The Prayer Book definitely provides for sacramental confession. It is true that this provision, in its specific form, is found only in the office of Visitation of the Sick. But its very clear position there simply presupposes its common use in time of health — otherwise the Church must be accused of employing very bad psychology indeed; for in that case her ministers are required to urge upon their people, under physical and emotional stress, some- thing of which these are presumed never before to have heard — and an emotionally upsetting matter at that!

Certainly a congregation in which the mention of "confession" is taboo can hardly be classed as a Prayer Book parish. Indeed, one might go further and say that, to meet this requirement, there must be some announcement of the hours at which the clergy are available for this ministry of absolution.

RULE OF LIFE

The Prayer Book offers a simple yet all-demanding "rule of life": "My bounded duty is to follow Christ, to worship God every Sunday in his Church; and to work and pray and give for the spread of the kingdom."

Here is a rule that is raised from the status of mere rule by the summons at the head "to follow Christ." The words of William Temple, used in the Presiding Bishop's sermon to General Convention and also in the pastoral letter of the House of Bishops, again bear repeating here: "Pray for me, I ask you, not chiefly that I may be wise and strong or any other such thing (though for these things I need your prayers); but pray for me chiefly that l may never let go the unseen hand of the Lord Jesus, and may live in daily fellowship with Him."

It is against the background of this evangelical imperative — "to follow Christ" — that the other four parts of the Prayer Book rule of life must be seen. Churchpeople may well ask themselves whether they regard the public worship o f God every Sunday as a moral obligation; how faithfully they say their prayers at home; how much of their time and talent they give to God's work; what portion of their income they regard as belonging to God.

While the several parts of this rule will ever be seen as obligation (or — if one prefers the Anglo-Saxon, Prayer Book term to the Latin — as one's "bounden duty"), yet to the person who sets himself to follow Jesus Christ as his Lord and Saviour." who loves our Lord for what He is and has done, no catalog of rules can exhaust the measure of love's response; and the character of the "precepts of the Church" as "obligations" will be overshadowed by the fact that they confer privilege and opportunity as well.

PRAYER BOOK "IDEOLOGY"

Finally, the Prayer Book contains a superhuman, supramundane ideology. As against the assumption, still widely prevalent, that man can pull himself up by his own bootstraps, the Prayer Book declares unequivocally that "we have no power of ourselves to help ourselves." The Prayer Book religion is a religion of grace — of transcendent power from above , specially channeled through the divine society, the Church, to meet human need at every level. Only through the reality of grace, available by prayer and sacrament, can holiness (also a reality) replace the reality in our lives of sin.

This is the ideology to which Churchpeople in their Sunday worship pay lip service. Either it is true or it is false. If it is false, it is dishonest to profess to on Sundays. But if this ideology be true, then it is true seven days out of the week; and any and every solution to life's problems that fails to take it into account is unrealistic. If, for example, sacramental grace be a power objectively real, then a husband and wife's neglect of Holy Communion may well be a factor as potent in the break-up of their marriage as any other.

If the Prayer Book ideology be true, it is relevant; and relevant to the whole of life. Yet in their discussion of contemporary problems — personal, social, economic, political — how many Churchpeople argue as if the reality of divine grace could have anything whatever to do with the matter? It is our observation that, outside of the Church building, Churchmen exhibit all too frequently a humanistic way of thinking that distinguishes them hardly at all from their secular neighbors.

We do not take seriously the grace of God, as a functioning reality in our lives. For all of us, the Payer Book ideology, and unashamedly to proclaim this to the world. In what better way can Churchpeople round out the Prayer Book quadricentennial that draws to a close — and gird them- selves to the task of evangelism that lies ahead?

1662IE, p. 247 "Then the minister shall declare unto the people what holy days or fasting days are to be observed in the week following."

1662IE, xxiv to lvii

1662IE, pp. 49-240

1662IE, xxv