Your entire hymnal should be memorizable by your congregation.

What does one do with church music?

(Part of a series on Anglican mission)

Continuing the footnote shared in a previous piece:

What, then does one do with the music?

Psalter as the main source of music—meterical1 or plainsong2—would be ideal, but most at an existing parish would not quite be up for such a radical demotion of the Hymnal 1940, 1982, Hymns Ancient & Modern, or the 2017 hymnal. So one must continue with the materials available.

If the purpose of ceremonial custom is to remove distractions—for distractions are what draw a people out of worship into the thing that distracts—it is extremely important for the gathered community, small or large, to sing songs everyone is capable of singing. The best, easiest way to do this is with songs they already know.

From The Case for Shorter Hymnals by John Ahern:

Your entire hymnal should be memorizable by your congregation. That should be the norm. After all, Jesus requires your congregants to worship him, and he most certainly does not impose music literacy as a prerequisite. (And, ideally, the same is true for literacy too.) So all your hymns should be easily learnable or easily memorizable, to the same degree that your liturgy is. This is another respect in which past practice can help us. It is why most hymnals historically have not been notated at all or had only melody (and it might even be a healthy practice to return to this, but I will leave that for another “question” of my “summa,” since that courts too much controversy for a single post).

Biblically, to know something is to memorize something. To have something in your heart, as a part of you, is to memorize it. This is a crucial theme of many psalms, not least Psalm 119, where we are encouraged to hide God’s word in our heart, bind it to our fingers, have it at the ready. To memorize something is not merely to know it, but to know through it; as C. S. Lewis says in God in the Dock, not to see the beam of light but by the light to see everything else. Not merely wissen but kennen, not merely savoir but connaître. This, as Mary Carruthers has effectively demonstrated in The Book of Memory, was the central task of singing the Psalms for the Christian church in the Middle Ages: to have the Psalms within you wherever you are.

The same should be true of hymns. Congregations should have a few hymns which go with them wherever they are in life, that travel with them through suffering and pain, that spring to their lips unbidden at every moment. That is simply impossible with a vast number. So long as our hymnals are a mile wide and an inch deep, so will be any connection between our spiritual lives and our church music.

To this end, Nashotah House Press has published an edited a collection of 100 Hymns for the Anglican Patrimony: A Hymnal of the Heart

From the INTRODUCTION:

Of the making of hymnals, there is no end. Why, therefore, this one? What sets it apart? First, It is intentionally short. It was inspired by John Ahern’s 2021 essay The Case for Shorter Hymnals in which he writes,

“We should have hymnals of, at most, 100 hymns... shorter hymnals capture the essence of what a hymn is for... your entire hymnal should be memorizable by your congregation... Biblically, to know something is to memorize something. To have something in your heart, as a part of you, is to memorize it... The same should be true of hymns. Congregations should have a few hymns which go with them wherever they are in life, that travel with them through suffering and pain, that spring to their lips unbidden at every moment. That is simply impossible with a vast number.”

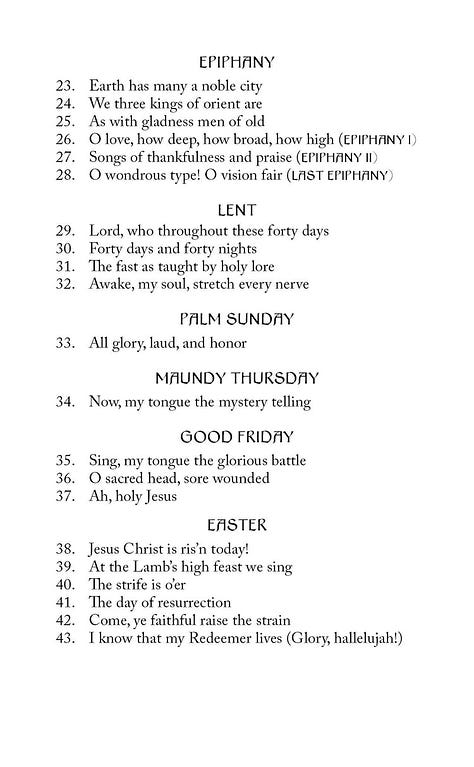

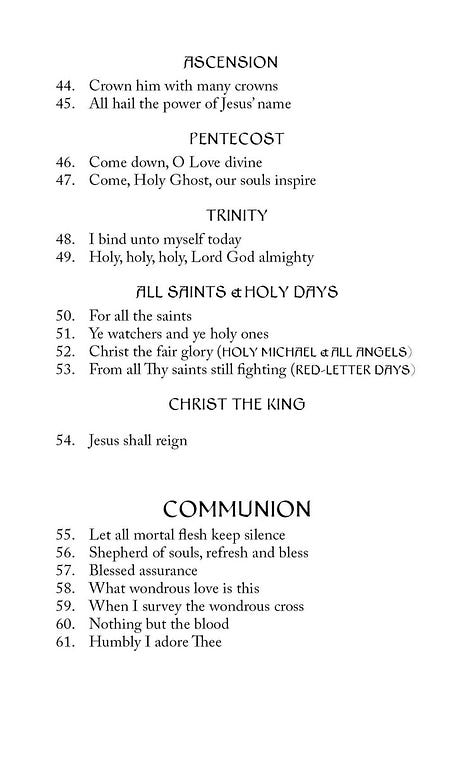

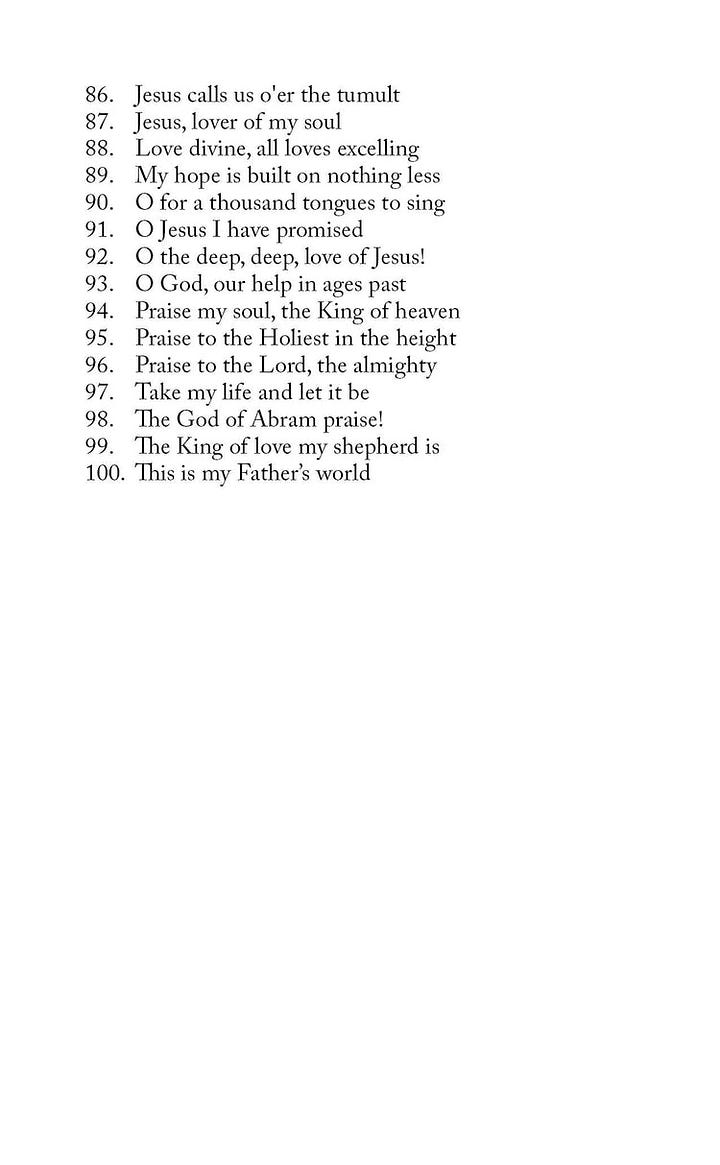

These 100 hymns represent the core of the English hymn tradition. Fifty map on to the Liturgical Year, and fifty are general songs of worship.

Second, only the melody line is given. This makes the tune easier to follow for those without a musical background. Additionally, it underscores congregational unity, as well as the priority of text over music, which assists the theological forming effects of the hymns. As Bonhoeffer writes in Life Together:

“Because it is bound wholly to the Word, the singing of the congregation... is essentially singing in unison... the simplicity and frugality, the humaneness and warmth of this way of singing is the essence of all congregational singing... This is singing from the heart, singing to the Lord, singing the Word; this is singing in unity.”

The typographical choice of placing all but the fist stanza in poetry form is intended to further make the words the focus of this hymnal.

Note especially that, for those who are leading the music, much of this is possible without changing most hymnals. Since these are known, public domain hymns, one could simply lead out of this pool of hymns from the church’s existing supply of hymnals, supplementing the occasional days where the hymn might not be in it.

What of newer songs? Well, that’s up to the church and what it can handle while retaining reverent space befitting the prayer book: the service, the hymns, are subordinated to the Liturgy of the Holy Communion. But it is not the end of the world to be a traditional church, be it classical “Prayer Book”, Anglo-Catholic, etc. and play songs written after the Victorian era . C.S. Lewis said of the Church of England

"I disliked very much their hymns, which I considered fifth rate poetry set to sixth rate music. But as I went on I saw the great merit of it. I came up against different people of quite different outlooks and different education, and then gradually my conceit just began peeling off. I realized that the hymns (which were just sixth rate music) were, nevertheless, being sung with devotion and benefit by an old saint in elastic side boots in the opposite pew, and then you realize that you aren't fit to clean those boots." (God in the Dock)

For Traditionalists, this devotion is important to remember in the opposite direction: someone could be having far more personal devotion singing Make My Life a Prayer to You A Capella than the complex counterpoint of a Dearmer hymn. While the service itself follows the words of the Prayer Book, there is not the same fixidity in the music of the parish. Many Traditional Anglo-Catholics would be as aghast as Lewis hearing the 5th/6th rate hymn in the 1940 Hymnal, hearing a Keith Green song—however arranged—or Hillsong’s This I Believe. We’ll leave aside—in this case—the issue of what instruments, if any, does one use.3 Personally, if the entire congregation knows how to sing (nearly) every song in the service, there is far less need for supporting instruments, piano, organ, guitar, etc. These may be supports—that is, instrument helping hold up the congregation as they build confidence—but it is a wonderful thing to have a room capably singing with just the Sacred Harp God gave each person.

{ιμκ☩}

Songs linked or referenced in this:

On the point of writing new lyrics and music: “Practically speaking, does this mean to stop singing in church any hymn more than a hundred or so years old? Stop reciting the Apostles’ Creed? Stop using the Westminster confession (or whatever)? Not at all. The principle of growth means we have to move on, but it also means we cannot move on until we understand our heritage. To try to generate good church music out of the meager vocabulary of American popular music is like trying to generate good theology out of the ideas heard on Christian radio and television. Christian theologians need to acquire familiarity with the whole of the Christian past, in constant contact with the primary special symbols, in order to move forward into new man-made theologies. Christian musicians must know all the music of the Christian past, in constant contact with the primary special symbols, in order to produce good contemporary Christian music.” from Symbolism and Worldview, James B. Jordan